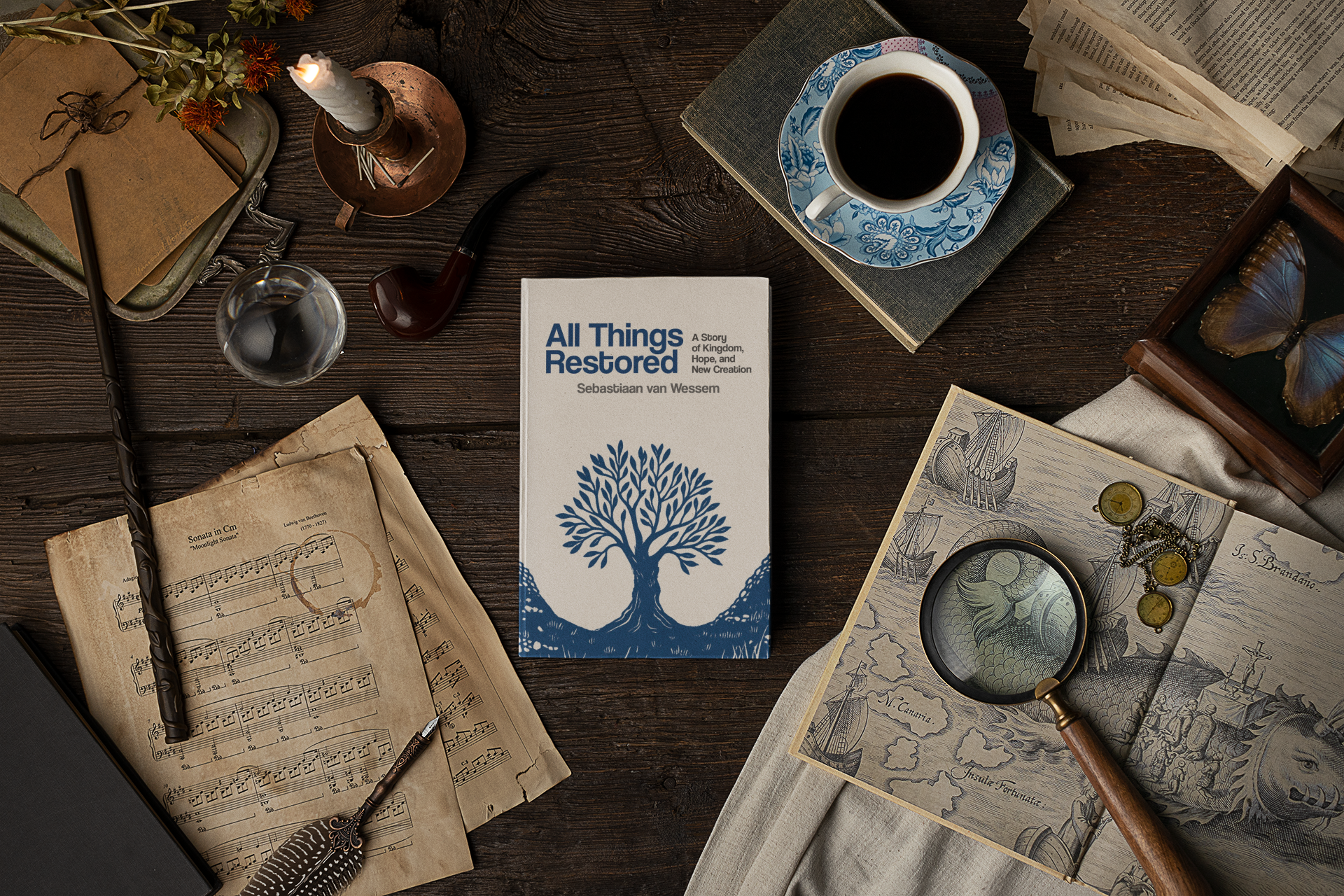

Want to get a taste of my book All Things Restored? This is the first chapter!

You can also download a PDF version, which also includes the table on contents.

Ready to purchase? This is where to go!

The Bible is much more than a collection of doctrines, laws, or moral tales. It is a unified story, a drama that begins in perfect harmony, is shattered by rebellion, and then moves relentlessly toward complete restoration. This story shapes everything: the way we see God, the way we see ourselves, and the way we see our mission in the world.

From Genesis to Revelation, Scripture traces a clear arc: creation, rebellion, redemption, and renewal. The story does not begin in a vacuum but in the beauty and order of a sacred garden called Eden. This first scene sets the trajectory of the entire biblical narrative. Eden is not simply “paradise lost.” It is the blueprint of God’s intent, the prototype of his Kingdom, and the destination toward which the story of redemption is headed.

Seeing the Bible as a single, coherent story is essential. Many modern readers approach it as a set of disconnected parts: laws here, promises there, moral examples scattered in between. But the ancient authors wrote within a narrative framework rooted in God’s ongoing covenant dealings with creation and his people. Understanding this storyline helps us avoid reading isolated fragments and instead see the unbroken flow of God’s purposes.

In this light, Eden is not just the beginning. It is also the goal. The entire history of redemption can be viewed as the story of God restoring his dwelling place with humanity in a temple-like new creation. That theme of restoration is the golden thread running through the Law and Prophets, the ministry of Jesus, the apostolic witness, and the prophetic visions of Revelation. From the first page to the last, the Bible ties the renewal of the world to the restoration of God’s presence among his people.

Seeing Scripture this way changes how we think about salvation and mission. The gospel is not an evacuation plan from creation but a rescue plan for creation. Our hope is not in an escape from this world but in the renewal of the world. Peter calls this “the restoration of all things” (Acts 3:21). To understand that restoration, we must return to where the story began: Eden, God’s first dwelling with humanity.

Eden as Temple and Sanctuary

Eden was not an ordinary garden. It was the first sacred space, the original meeting point of heaven and earth, where YHWH’s presence rested and his divine council gathered.[1] The biblical author describes Eden with imagery that is later echoed in Israel’s tabernacle and temple. God “walks” in the garden (Gen.3:8), just as he “walks” in the tabernacle (Lev. 26:12). Eden’s entrance faces east, just like the tabernacle’s entrance (Gen. 3:24; cf. Ezek. 43:1-4). Cherubim are stationed as guardians in both places (Gen. 3:24; Ex. 25:18-22). These parallels are intentional. From the very beginning, the Bible uses temple language to show that God’s dwelling with humanity is a central theme.

Gordon Wenham observes, “The garden of Eden is not viewed by the author of Genesis simply as a piece of Mesopotamian farmland, but as an archetypal sanctuary – a place where God dwells and where man should worship him.”[2] Michael Heiser adds, “Eden was God’s home on earth. It was his residence. And where the King lives, his [divine] council meets.”[3] That means Eden is both the first temple and the pattern for every sanctuary to come.

In the ancient world, temples were often located on high ground to symbolize proximity to the gods.[4] Many Jewish and Christian traditions connect Eden with a mountain, specifically Mount Moriah, later known as Mount Zion, which is the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. The prophet Ezekiel links the images directly, describing Eden as “the garden of God” and “the holy mountain of God” (Ezek. 28:13-14). Ancient traditions from the Second Temple and early rabbinic era, such as Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer, even place Eden at the very site where the Jerusalem temple would one day stand, underscoring the continuity between God’s original habitation and his chosen place of worship.[5]

This “sacred geography” unites Eden and Zion into a single redemptive storyline: from the first garden‑temple, through Israel’s sanctuary, to the New Jerusalem (Isa. 2:2-4; Rev. 21:10). Even the rivers of Genesis 2 hint at this connection. One, the Gihon, has been identified by some ancient interpreters with Jerusalem’s Gihon Spring, the city’s ancient water source and a vital part of its temple rituals. Whether the geographical identification is precise or not, the symbolism is powerful: temple, spring, and mountain all come together as enduring images of God’s life-giving presence.[6]

Eden, then, is not just the backdrop for humanity’s beginning. It is the archetype of where creation is heading. Jerusalem stands as a prophetic echo of Eden, and points to the New Jerusalem where its consummation will be – a restored sacred city where God dwells with his people forever.

Humanity’s Priestly Calling and the Image of God

In the very beginning, humanity was created in the image of God (tselem elohim, Gen. 1:26-28) and entrusted with dominion over creation. This dominion was never intended as domination. It is sacred stewardship, a partnership with God in caring for what he has made. Genesis describes humanity’s vocation using priestly language: “to cultivate it and keep it” (Gen. 2:15 BSB). As G.K. Beale notes, the Hebrew verbs used here, ʿābad (“serve”) and šāmar (“guard”), commonly refer to priestly duties in Israel’s sanctuary, so the author of Genesis has sacred service in mind, not just agricultural labor (Num. 3:7-8; 18:5-6).[7] Humanity’s task in Eden, then, was to be royal priests: representatives of God’s rule and caretakers of his temple-garden.

This priestly vocation reaches deeper than mere responsibility. In the ancient Near East, kings were often described as “images” of the gods, mediating the authority of the gods on earth. But Genesis democratizes this dignity: every human being, not just the elites, is called to image the God who created the universe, share his kingship, and reflect his character. As Michael Heiser writes, “We are God’s representatives on earth. To be human is to image God.”[8] We are God’s representatives – his earthly council and administration. To bear God’s image is to actively participate in his purpose for creation.

Carmen Joy Imes takes this further by arguing that bearing God’s image includes bearing his name, which is a call to represent him relationally and ethically, to carry his reputation and character into the world. This priestly identity is not just about status. It is about vocation. Human beings are meant to be visible reminders of who God is – living as ambassadors, mediators, and witnesses to his justice, mercy, and holiness.[9]

This original purpose undergirds the whole biblical story. Sin distorts the image but redemption in Messiah restores it. In Jesus, humanity’s priestly calling is renewed, not just so that we could be saved individually but that our whole vocation of worship, stewardship, and witness can be restored (Rev. 21:22-27). The priesthood of all believers now means every follower of Jesus is called to take part in tikkun olam – repairing and restoring the world by extending God’s mercy, pursuing justice, and manifesting his presence.[10] Our participation in God’s mission is not peripheral but central. We are called to help creation reflect the character and rule of its Creator (Micah 6:8).[11]

Becoming Part of God’s Family

To be created in God’s image is, at its core, to be welcomed into his family. From the opening chapters of Genesis throughout the whole Bible the relationship between the Creator and humanity is framed in terms of kinship: God as Father, humanity as his children (Luke 3:38). Just as children resemble their parents in appearance and character, human beings were meant to reflect their Father’s likeness and ways, both in who they are and in what they do.

This family identity is not static. It comes with a calling. To be a child of God is to take part in the “family business”: tending, governing, and blessing the earth under his authority. Michael Heiser describes Adam and Eve as “Yahweh’s choice to be steward‑kings over a global Eden under his authority,”[12] a role that combines both royal responsibility and intimate relationship. Eden, therefore, stands as the prototype of a family‑Kingdom: God’s dwelling with his people, his reign mediated through his sons and daughters, and his presence filling creation.

The story of Scripture continually returns to this theme of divine family. Israel is called God’s “firstborn son” (Exod. 4:22; cf. Eph. 2:19), chosen to reflect his character to the nations. In the New Testament, believers, both Jews and Gentiles, are adopted into God’s household through Messiah Jesus, “the firstborn among many brothers” (Rom. 8:29; Gal. 4:4-7). Through union with him, the family Adam was meant to begin is finally restored and expanded.

This identity also transforms our posture in God’s mission. We are not distant subjects serving an impersonal ruler, but sons and daughters representing our Father’s interests in the world. We are his ambassadors (2 Cor. 5:20). Our stewardship is relational, rooted in trust, love, and shared purpose, not in fear or compulsion. As members of God’s royal household, we bear his name and extend his blessings to the nations, anticipating the day when this reality reaches its fullness in the new creation, “when… the dwelling place of God is with man” (Rev. 21:3).

Vatican City (1510–1564)

Exile from Eden: The First Rift

The narrative of Genesis quickly turns from intimate communion to a tragic disruption. The Fall (Gen. 3) damaged God’s original order, and the consequences reached every corner of creation. Yet this moment of rebellion is not an isolated event. Scripture traces a trilogy of primeval rebellions: humanity’s disobedience in Eden (Gen. 3), the corruption that brings the flood in Noah’s day (Gen. 6:1-4), and the idolatrous unity at Babel (Gen. 11:1-9). Each episode deepens the separation between God and humanity, marking a pattern of exile and alienation.

Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the garden (Gen. 3:23-24) was far more than a change of location. It marked the loss of access to God’s presence, the loss of humanity’s priestly vocation, and the beginning of a deep rift within creation itself. Where humans had once enjoyed direct fellowship with God as royal priests, they were now driven east of Eden, exiled and longing for the restoration of all that had been lost.[13]

The exile motif becomes a central theme in the biblical story.[14] We will see it again when Israel is expelled from the Promised Land. The theme of exile is used as a symbol for all kinds of alienation: spiritual, relational, and societal. Sin not only drives a wedge in the relationship between God and humanity but also breaks their relationships with one another and with creation. Paul describes this state as a life under the “domain of darkness” (Col. 1:13). The image of God in humanity is marred, and the mission to serve and reflect him is disrupted, leaving creation fractured and incomplete, longing for its renewal (Rom. 8:19-21).[15] Yet even in exile, the promise of restoration begins to take root. The biblical drama now turns toward the hope that God will not abandon his family but will make a way for them back home.

The Restoration Theme Begins

Even in the midst of judgment, God plants a seed of hope. In Genesis 3:15, often called the protoevangelium (“first gospel”), God speaks of ongoing conflict between the serpent and the woman, and between their offspring: “he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel.” This promise, though brief and cryptic in its original setting, becomes the seedbed for the Bible’s restoration story.[16]

To ancient Israel and to the early Church, this verse signaled more than a clash of good and evil. It pointed to a final victory. The serpent, emblem of rebellion, would one day be crushed. Many Christian interpreters, from the Church Fathers to modern scholars, have understood the “seed of the woman” as a prophetic anticipation of Messiah, the one who would undo the damage of Eden, defeat the adversary, and restore creation to its intended harmony.[17]

This promise is important not just because it predicts victory but because it is the first hint of hope that runs through the whole Bible. Later prophetic passages pick up the theme: the son of David who will rule in righteousness (Isa. 9:6-7), the servant who will bring healing and justice to the nations (Isa. 42:1-9), the King whose reign will reverse the curse and bring peace even to creation itself (Isa. 11:1-9). The New Testament writers see these threads converging in Jesus, whose life, death, and resurrection begin the ultimate reversal of the tragedy of Eden and the other two primeval rebellions.

From this moment forward, the Bible’s narrative is set on a trajectory toward restoration. The exile from Eden will not be the final word: a Deliverer is promised, the enemy will be defeated, and the presence of God will once again dwell with his people.

Pastoral Reflection: Eden, Identity, and the Church Today

Why does the story of Eden matter for pastors and leaders today? Eden provides three essential anchors: identity, mission, and hope. First, Eden reframes our identity; it reveals who we truly are. We are not only defined as sinners in need of rescue but as image‑bearers called to live as royal priests, destined to reign in Jesus’ name with his delegated authority (Rom. 5:17). When the Church understands itself in light of God’s original design rather than merely as exiles from Eden, it changes how we teach, disciple, and lead. Our message is not only about escape from sin but about a restoration to our true identity and calling.

Second, Eden redefines our mission. The gospel is not simply about getting people into heaven but about forming a community that reflects God’s presence and reign on earth. The New Testament pictures the Church as a mobile temple, a “garden‑people” whose life brings healing, justice, and fruitfulness wherever they go (Rev. 22:2). So, pastors should encourage their congregations to take an active, visible part in God’s work of renewing the world through worship, discipleship, and shared life together.

Finally, Eden gives us hope. Restoration is not wishful thinking – it is the heartbeat of Scripture. God’s purpose is to renew all things under the reign of Messiah. Our ministry is not merely to lead individuals to salvation but to join him in the renewal of reality itself: families, neighborhoods, creation, and ultimately the whole world. The story is not over, and our calling carries far more dignity and hope than we often realize. Every act of faithfulness, every work of love, every glimpse of beauty is a foretaste of the world to come: the beginning of Eden restored.

“Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man.

He will dwell with them, and they will be his people,

and God himself will be with them as their God.”

(Revelation 21:3)

Want to Go Deeper?

This post only scratches the surface.

All Things Restored traces this story from Eden to the New Jerusalem, showing how Scripture consistently points toward the restoration of creation, the renewal of Israel and the nations, and the return of the Messiah.

If this vision resonates — if you’ve sensed that the gospel is bigger than you were taught — this book was written for you.

👉 Discover the full story in All Things Restored.

Footnotes

[1] Michael S. Heiser, The Unseen Realm: Recovering the Supernatural Worldview of the Bible (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2015), 44-48. Heiser’s book builds a compelling case for lower elohim (spiritual beings) who are created by YHWH who serve with him on a divine council. A great example is Psalm 82, but there are many other passages in the Hebrew Bible that support this idea. I often use YHWH in this book instead of “God” or “the Lord.” YHWH is the transliteration of the Hebrew letters yod-hay-vav-hay in the Old Testament, which is the covenant name of God. Since according to Jewish tradition no one knows how to pronounce this name, I will refrain from using vowels and stick to what the Biblical text presents us. YHWH is also called the “Tetragrammaton” (Greek for “four letters”).

[2] Gordon J. Wenham, “Sanctuary Symbolism in the Garden of Eden Story,” in Proceedings of the Ninth World Congress of Jewish Studies (Jerusalem: World Union of Jewish Studies, 1986), 19.

[3] Heiser, The Unseen Realm, 44.

[4] L. Michael Morales, The Tabernacle Pre-Figured: Cosmic Mountain Ideology in Genesis and Exodus, A dissertation submitted in completion of requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy, University of Bristol / Trinity College, 9 May 2011, p.2.

[5] Pirkei DeRabbi Eliezer, trans. Gerald Friedlander (London, 1916), ch. 12, https://www.sefaria.org/Pirkei_DeRabbi_Eliezer.12.1, accessed on July 8, 2025. This early rabbinic midrash retells and expands the biblical narrative from Genesis through Numbers, including ethical teachings, ancient Jewish customs, legends, and calculations concerning creation and the end of days. Traditionally attributed to Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus, a 2nd‑century sage, it was likely edited in the 8th or 9th century. In 12:1 it reads: “With love abounding did the Holy One, blessed be he, love the first man, inasmuch as he created him in a pure locality, in the place of the Temple, and he brought him into his palace, as it is said, ‘And the LORD God took the man, and put him into the Garden of Eden to dress it and to keep it’ (Gen. 2:15)….”

[6] Stephen L. Cook, “The Temple in the Christian Bible,” St Andrews Encyclopaedia of Theology (Aug. 2023), https://www.saet.ac.uk/Christianity/TheTempleintheChristianBible (accessed on 21 Nov. 2025).

[7] Beale, A New Testament Biblical Theology (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2011), 617-618.

[8] Heiser, The Unseen Realm, 43.

[9] Carmen Joy Imes, Bearing Yhwh’s Name at Sinai – A Reexamination of the Name Command of the Decalogue (University Park, PA: Eisenbrauns, 2018), 178-179.

[10] Anna Beth Havenar, “Repairing a Broken World: The Jewish Concept of Tikkun Olam,” Light of Messiah Ministries Blog, 6 Feb. 2024, https://lightofmessiah.org/blog/repairing-a-broken-world-the-jewish-concept-of-tikkun-olam (accessed on 21 Nov. 2025).

[11] In Jewish thought, especially within Second Temple Judaism and later rabbinic tradition, tikkun olam captures the idea that God’s people are called to participate actively in healing and restoring all aspects of creation, with the goal to bring about social justice, righteousness, and peace. It’s a holistic mission that goes beyond personal spirituality to include restoration of relationships and society.

[12] Heiser, The Unseen Realm, 56.

[13] The Bible states that after the fall, humanity moved east of Eden in Genesis 3:24: “So he drove out the man, and at the east of the garden of Eden he placed the cherubim and a flaming sword that turned every way to guard the way to the tree of life.” Additionally, after Cain killed Abel, we read in Genesis 4:16: “Then Cain went away from the presence of the Lord and settled in the land of Nod, east of Eden.”

[14] Bryan D. Estelle, “The Exodus Motif in the Christian Bible,” St Andrews Encyclopaedia of Theology, https://www.saet.ac.uk/Christianity/TheExodusMotifintheChristianBible (accessed on 21 Nov. 2025).

[15] See Beale, A New Testament Biblical Theology, 384. Beale explains that after the fall, Adam and Eve were no longer able to fulfill humanity’s original mandate to reflect God’s image and fill the earth with his glory; rather, their efforts became frustrated and marked by sorrow, signaling a loss of their intended vocation.

[16] C. John Collins, Genesis 1-4: A Linguistic, Literary, and Theological Commentary (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2006), 155-159, 176-178.

[17] Kevin S. Chen, The Messianic Vision of the Pentateuch: A Biblical-Theological Introduction to the Messiah and His People (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2019), ch.1.

Leave a Reply